In this article

Engineering managers and leaders often obsess over velocity and process – and forget about the more hidden factors like satisfaction of your engineers. One underappreciated lever of sustainable software success is the manager-to-engineer (MtE) ratio. This seemingly trivial metric can dramatically impact team productivity, developer satisfaction, and company-wide scalability.

There is no universally accepted “perfect ratio” but studies consistently reveal that suboptimal ratios can silently corrode your culture, slow your teams, and jeopardize long-term retention. Most high-performing engineering organizations – including Google, Microsoft, and Amazon – have ratios around 1:6-9 (that’s one manager for every six to nine engineers).

At the lower end, Netflix operates a flatter organisational structure with ratios of 1:5-6, while on the higher side, Meta sometimes stretches to 1:12, relying heavily on autonomous senior ICs.

As subtle as these differences in ratios may seem, they influence the texture of engineer’s daily experience and team sentiment.

When Ratios Drift, Culture Erodes

When Ratios Drift, Culture Erodes

Engineering teams suffer when the MtE ratio drifts too far in either direction – too low and the risks of micromanagement, overhead, and loss of autonomy emerge – too high and managers are stretched thin, unable to coach and support, and likely to miss challenges their team might face.

A study by Microsoft in 2008 found that teams with managers overseeing more than 10 engineers consistently reported higher rates of defects (Nagappan et al. 2008). The problem wasn’t the process of the team, instead it was caused by the fact that the managers simply did not have the bandwidth for mentorship and code review and that quality quietly suffered as a result. Consequences can also show up in team connectivity especially if teams are located in different geographical locations. Verner et al., 2014 found that when managers were absent or unable to give attention and coaching, engineers disengaged not only from the work but from the organization itself (represented in low organizational commitment scores). What’s more, engineers in this group reported far higher intentions to leave even while still enjoying their day-to-day tasks.

Worst yet, stretched managers aren’t just less available – they may inadvertently dismantle psychological safety since wide ratios often mean less communication across cultural or regional boundaries (Randeree and Chaudhry, 2007). These effects are often deeply felt, but rarely visible on dashboards.

Ratio in Practice: What We Learned from 445 Companies

Ratio in Practice: What We Learned from 445 Companies

We analyzed manager-to-engineer ratios across 445 companies from several different sectors ranging from five to thousands of engineers and confirmed some of these previous findings.

Across our dataset, the average MtE was 1:5 – one manager for every five engineers – indicating that while literature and anecdotes often reference wider spans (e.g. 1:8 or more), the reality of working ratios in functioning organizations tends to remain tighter.

Ratios do not vary when comparing companies of different sizes, though companies with fewer than 500 employees also tend to have slightly lower ratios (1:4 – 1:5 compared to 1:5 – 1:6).

Across industry verticals, the highest engineer-to-manager ratios were found in Finance & Business Services and Industrial/Manufacturing sectors (up to 1:7.8), which often rely on standardized processes and mature delivery pipelines. By contrast, Healthcare, Energy & Utilities, and Education sectors maintained the lowest ratios, likely reflecting regulatory complexity, critical uptime needs, and organizational conservatism.

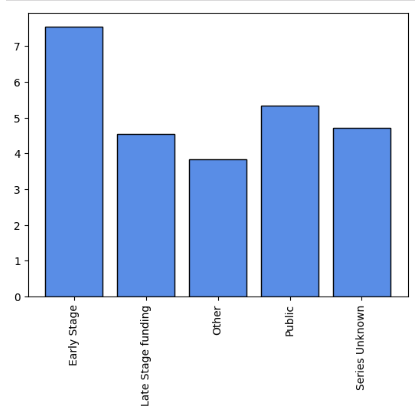

Interestingly our data shows that early-stage companies do not always have a flat culture with low MtE ratios; in fact early state companies (Seed, Series A, and Series B funded companies) have much higher MtE ratios than companies in later stages. On average, companies at these stages have ratios of 1:7.5 while ratios for later stage companies are, on average, 1:4.6. This suggests that young startups might have to operate more flatly out of necessity, while more mature companies are able to reinvest in leadership structures as they scale.

The Ratio to Retention Link

The Ratio to Retention Link

The relationship between MtE ratios and engineer retention emerged clearly in our data: The average tenure for engineers in the dataset was two years and four months. Among engineers who left their companies, a striking 64% had managers with MtE ratios higher than the company’s average.

More granularly, engineers whose managers had one to six direct reports stayed at their company six to nine months longer (compared to the average). In contrast, engineers whose managers had 10 or more direct reports on average stayed for two years. That is four months less than the baseline.

These retention patterns were consistent across tenure levels, from interns to leads, and across common functional tracks like frontend, backend, and test engineering. Interestingly, engineers in roles like infrastructure, IT, and data science tended to have managers with fewer direct reports, reflecting either smaller team sizes or more deliberate management design.

Final Thoughts: Ratios as a Strategic Signal

Final Thoughts: Ratios as a Strategic Signal

Managerial bandwidth isn’t just a logistics issue – it’s a lever for culture, cohesion, and long-term sustainability.

When engineers don’t feel supported, guided, or coached, they might not disengage from the work – but instead disengage from the company. When managers are overextended, the cracks don’t show up immediately in Jira – they show up in turnover, mentorship gaps, and quiet underperformance. These effects compound silently, often long before you see them on a dashboard.Your manager-to-engineer ratio is not just a staffing number. It’s a cultural signal, a retention predictor, and a strategic design decision. And it should be treated as such.

How do your engineers really feel?

Happy engineers are more productive team members. Learn how to measure engineer sentiment, build trust and promote a happy, healthy and efficient team.

Download the Ultimate DevEx PlaybookAbout the author

Lena Chretien, PhD, is a Senior Data Scientist at Jellyfish.