In this article

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared on Engineering Together, a newsletter by Adam Ferrari. Adam is an Advisor to Jellyfish and the former SVP Engineering at Starburst and EVP Engineering at Salsify. You can subscribe to Adam’s newsletter here.

I previously wrote about the importance of a clear and consumable product strategy doc for the Engineering organization. On the one hand, I know, duh. But I find it a surprisingly underappreciated topic, and I’m sure I’ll come back to it. One closely related idea is the surprisingly powerful idea of an investment allocation model.

Every software R&D org, intentionally or unintentionally, is making a variety of different types of bets. It can’t be avoided since supporting and creating software products involves a range of different types of activities. This includes everything from building new products and features, to adding functionality to existing products, resolving customer issues and bugs, and improving technical architecture in order to make all of the above more efficient and predictable, and more. Like it or not, you are placing dollars onto the R&D roulette table in all of these different betting areas and hoping to maximize the payout for your company.

R&D leaders are always acutely aware of making the most of their scarce resources. One of the wonderful but also frustrating things about working on software products is that there are often tons more interesting and promising ideas than the number you can actually pursue. Making hard choices and saying “no” to some of the good ideas is mathematically part of the job. There are many strong tools for helping with this problem, but one really simple and powerful tool is ensuring you have a strong model and process for managing investment categories and allocations.

My appreciation of the importance of a strong allocation model came into extra focus in 2022 as the industry shifted quickly from the ZIRP “growth at all costs” mindset to “efficient growth (but, above all, efficiency!).” My company, like so many growth stage tech companies, found itself suddenly out of step with investor expectations, which forced us to adjust our posture quickly to one of efficient growth. We worked with one of our largest investors, who had a strong program for supporting R&D leadership, to clarify our ROI framework and model for investing efficiently.

Of course, an overall framework for efficient ROI-driven product execution is a huge topic, spanning everything from prioritization to measuring outcomes and everything in between. But developing a solid model for investment categories and allocations is a surprisingly good start to a strong overall approach, and has big implications for the Engineering function in particular.

The Basics of an Allocation Model

The Basics of an Allocation Model

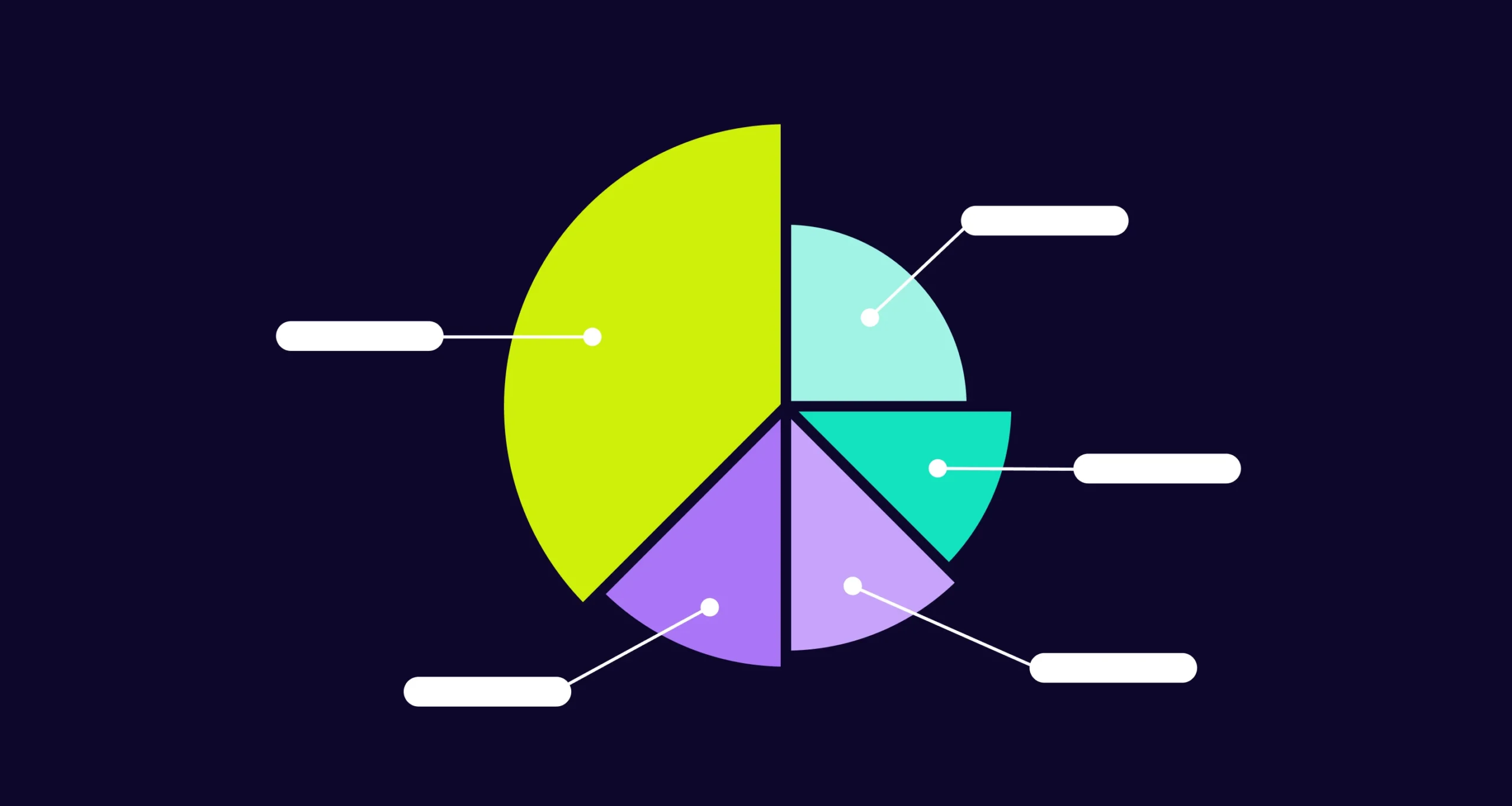

For starters, what does an allocation model even look like? Luckily the model itself is not a complicated thing. The interesting work comes from deploying the model. The following picture shows a simple version of an allocation model, similar to what my previous organization ended up using:

The target allocations here are a guideline that we developed with our investor based on their portfolio company benchmarks over time. But the values are truly just an average, and the balance absolutely may need to shift depending on the specific challenges the company is facing.

The categories have the following definitions:

- Innovation: This is the good stuff, essentially delivering new or improved functionality including new or improved products and features of existing products.

- Innovation – Current Growth: This represents innovation work that is expected to deliver incremental revenue in the one year or less timeframe. This can be thought of as work to grow your “Sales Obtainable Market” (SOM), in other words what can you sell and deliver today (or soon).

- Innovation – Future Growth: This represents larger innovation work with a longer than one year payout – i.e., the big long-term bets. This includes work to expand the company’s total addressable market (TAM), such as taking on fundamentally new types of customers or use cases, adjacent to but outside of the company’s current offering.

- Customer Retention: This is work specifically driven by existing customers to maintain or reduce churn and / or downsell. Where innovation work is meant to make revenue go up, customer retention work is intended to prevent it from going down.

- Technical Investments: This is work driven by the Engineering team intended to improve the efficiency of the company, usually Engineering itself. For example, this work could be everything from adopting a new more powerful framework, re-working your CI/CD strategy for faster / easier / more reliable builds, improving internal enablement, factoring similar functionality into a shared artifact, etc. The payoff of these investments is in improved output over time. This of course translates to customer value, but the effect is one step removed.

- Keep the Lights On (KTLO): This is the work you don’t select, but rather it emerges as a function of running the business. This includes fixing issues identified by customers, patching CVEs as they are detected, upgrading dependencies in a timely fashion, etc. This is the most frustrating category for most R&D teams since you can’t directly control the allocation. Work emerges and it has to get done, which means you need to plan for enough capacity to handle it and still meet customer and compliance commitments such SLAs on responding to issues. The only real way to reduce spend in this area is to make investments to improve factors like quality, maintainability, developer tooling, etc., e.g., more investment in quality may bring down the time spent on customer reported issues.

These may not be the exact buckets that are right for your business. For example, one common addition I’ve seen frequently, especially in businesses that sell to very large / global enterprise organizations is to have a “Customer Specific” investments bucket to account for investments that are critical to a single strategic account. But this gives a good general starting point from which to work.

A Note on Designing for Outcomes

Whatever categories you pick, one of the most valuable design principles that you can employ is to pick categories with a clear and single value outcome. In other words, investments in a given category should all be intended to produce the same type of value. For example, “Innovation: Current Growth” category investments should all create outcomes like more pipeline, more ARR, etc, in the “less than one year” timeframe. All of the “Customer Retention” investments should result in the associated issue getting cited less frequently in churn / downsell reports, and thus reduce the amount of churn and downsell.

Benefits of the Model

Benefits of the Model

The benefits of this type of design are (at least) twofold. On the one hand, it makes the relationship between outcomes and investments very direct. Want more near term revenue growth? It’s clear which bucket to increase. This makes the model a good tool for collaborating with the business around the product roadmap and strategy.

Secondly, it makes prioritization clearer by organizing candidate investments into groups of comparable items. If we’re looking within a bucket – for example, what are the most compelling TAM expanders we can work on? – then prioritizing one investment over another makes perfect sense. Pick the investments that will drive the best outcome of that type. But when you find yourself comparing investments across buckets, you’re in a strange zone. You’re actually debating the relative priorities of the buckets.

Of course the business needs to prioritize across everything. When you fund a project you are implicitly directing that investment away from all of the other possible projects. But really, how can you possibly compare the ROI of a tech investment that will make delivery more efficient in six months or a year versus a near term ARR driver targeted to unlock a specific type of opportunity? It’s just an impossible “apples versus oranges” comparison. It’s SO much more productive to think about the types of outcomes you need and their relative / proportional priority, and then separately consider the best investments available to drive each outcome. It’s a better conversation, and usually more pleasant for everyone involved.

Implications for Engineering Leaders

Implications for Engineering Leaders

1. Ensure a clear and accurate way to track actual investments by category

Setting allocation targets based on the various needs and priorities of your product strategy is a great start. But of course software projects are impossible to estimate perfectly (and, in fact, putting too much effort into estimation accuracy is its own pitfall). Tracking actual investment is important for a couple of reasons. There’s no perfect way to do this, but this is where having an Engineering Management Platform that can provide metrics such as FTE time per project can be extra helpful. I’ve used Jellyfish for this successfully (and much more!) in the past. (Disclosure: I’m currently working as an Advisor with Jellyfish)

Looking at actual spend helps set realistic expectations about relative progress in various areas (versus looking at a project by project level, which often fails to provide a high enough level view to be useful to exec management or the BoD). And in addition to providing a first order view as to whether you need to make adjustments to achieve your stated goals, the actual allocation is a check on whether your product strategy is truly affordable. If you find areas unavoidably being starved for resources, you may be spread too thin.

2. Set thoughtful targets for Engineering-driven categories like Technical Investments and KTLO

As described above, investment categories create a very rational and constructive way to discuss Engineering driven investments. For example, based on our market and competitive set, what kinds of platform investments do we need to make to achieve velocity and agility in the future? Those speedups don’t come for free, so how should we balance them against shorter term ROI?

One key aspect of setting these targets is ensuring that the non-discretionary investment – i.e., “Keeping the Lights On” – is accounted for appropriately. The truth is, unlike the other investment categories, this one is less “a target that you set” and more “an unavoidable bill you’ll have to pay.” After all, you can’t really ignore maintenance issues like a customer bug. Knowing actual past spend in the KTLO category will help set rational expectations for future spend in this area, and in turn help prevent setting unreasonable delivery expectations. This can include tactics like looking at KTLO as a function of adoption metrics such as number of customers, number of active users, etc. And if we expect KTLO to scale differently in the future than it has in the past, we should have an explanation for why (e.g., based on a technical investment and the maintainability improvement we anticipate as a benefit of that work).

3. Share allocations and their rationale with the team

While allocations are a valuable tool for R&D leadership to help connect the team’s investments to different categories of goals, they are also a powerful explainer for the team. It is so common for teams to want to do more than the company can possibly afford. And this tends to be especially true in terms of Technical Investments.

I’ve found that sharing investment allocations (along with product strategy) with the entire team is a powerful tool to clarify the compromises we must make. On the one hand, it can help highlight a healthy investment level that might otherwise be less appreciated in light of the many investments the team is unable to make (i.e., this helps combat the behavioral economic concept of “loss aversion” that we experience when an idea isn’t prioritized). And I’ve also found that it holds management accountable for honoring targets. If quarter after quarter we find that our actual spend on Technical Investments is far below our stated goal, something is definitely off.

Allocations, Simple but Powerful

Allocations, Simple but Powerful

“Breaking down the problem” is one of the most important and powerful concepts in software engineering. If we can take something complex and break it into smaller, simpler problems, we can implement solutions that are not just easier to understand, but that actually work.

The idea of investment categories and allocations is simply an instance of “breaking down the problem,” but for managing software investments. If we can break down the big complex universe of what needs to get done and put various problems and ideas into their appropriate buckets, priorities get easier to manage, and we make sure we attend to all of the various areas that need consideration. For software teams, where those areas span various groups and concerns, this is especially powerful. How can we make sure that Product doesn’t dominate all of our cycles at the expense of strengthening the tech? Or alternatively, how do we make sure the Engineering team maintains a healthy balance of “building foundations for the future” with “banking revenue-generating value today.” Getting intentional about allocations helps us balance these types of equations, and place a winning portfolio of bets for the business.

For more engineering insights from Adam, check out his newsletter, Engineering Together.

About the author

Adam Ferrari is an Advisor to Jellyfish. He is the former SVP Engineering at Starburst and EVP Engineering at Salsify. Subscribe to his newsletter, Engineering Together, here.