Story points have their place in Agile, but they leave much to be desired for engineering leaders. Engineering teams will continue to use story points for the foreseeable future, and this post isn’t an attempt to try to sway your teams from them. This post is not us picking a fight with story points; it’s acknowledging the limitations of them and explaining why they should not be used as the foundation for measuring your engineering organization’s strategic alignment to the business.

Story points are a necessary tool for Agile sprint planning

If there were a better alternative to story points, even for planning purposes, I imagine that teams would be rushing to try it. But they’ve been a mainstay of Agile for a reason.

Sprint planning teams need a way to measure all of the various factors that could impact the total work for a given task. Story points are a best attempt at assigning one value to represent the amount of work and risk involved for each task. And currently, story points are the only consistent way to communicate with project management about the effort that backlogged feature work will take. For these two reasons, story points have enabled the sprint planning model, and we expect them to continue to be used until technology or methodology improvements enable something better.

Story points don’t work for strategic alignment & retrospection

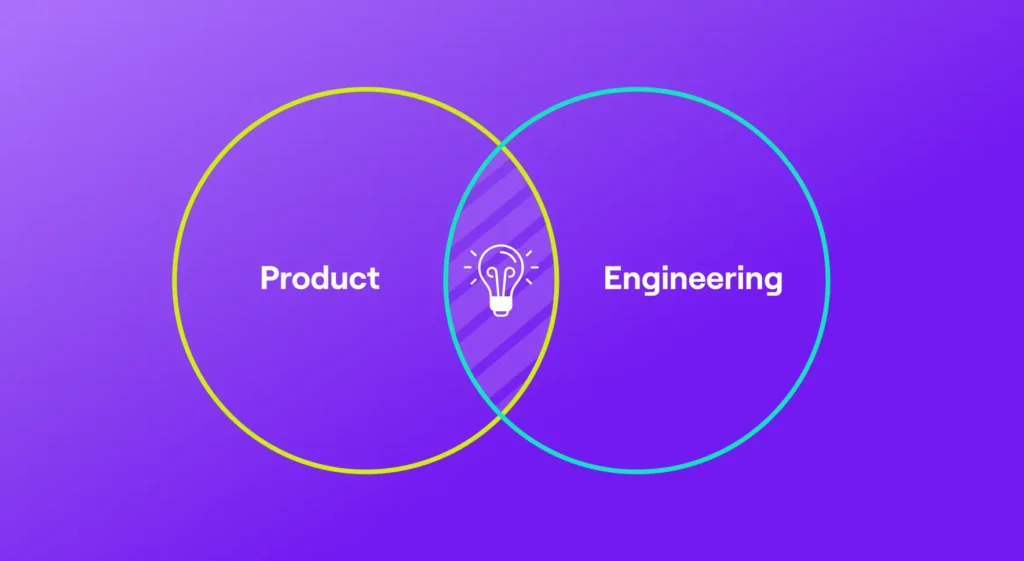

Story points work for trying to plan and assign tasks toward completion of a project on a given team, but we don’t recommend using them for representing engineering work across multiple teams, and especially for planning across functional organizations. Consider the scenarios when you as a leader would want to collect information regarding how your engineers have been spending their time. There are two primary reasons: to inform your decision-making and to report to your business peers.

For strategic decision making

For strategic decision-making, consider the types of insights that would help you. Productivity, efficiency, and Allocation (what your teams are working on) are top ones we hear from engineering leaders frequently. For any of those insights, what would a retrospective on the assigned story point value on the feature work actually provide you? Are you confident all of your teams are assigning story points consistently in the same way? For most teams, the reality is that their teams assigned story point values differently. Even if you could turn that effort estimation into an actual final value, and your teams follow the same criteria for assigning story point values, you would still need to translate story points into time to properly calculate recommended productivity, efficiency, or Allocation metrics. That’s a hard no for an Agile advocate, so let’s not use story points from the start for this specific purpose.

For reporting to the business

When reporting to your business peers, story points won’t translate to any other area of the business. And as soon as we become heads of engineering, we become responsible for translating engineering work into the language of the business. As a general rule of thumb, if we have to explain the metric to a business peer, we should probably try to find another metric first.

Additionally, story points also don’t translate easily to costs. When trying to evaluate where to invest engineering resources (likely a conversation with Product, and business leaders), understanding the costs of the products and features you’ve already built is extremely valuable. When reporting with story points, it’s nearly impossible to parse out the factors with costs associated with them from those that don’t (for example, risk vs number of engineering hours on a task). Leaders require a better unit of measurement for these purposes.

Why Jellyfish Measures Engineering Work In FTE Efforts

For strategic planning, leaders can represent the amount of engineering work on a particular feature, or initiative in terms of time. More specifically, they can represent engineering work in “Full-Time Engineers” or FTEs. Yes, doing this manually can be painful for everyone involved. There are exceptional organizations that have overhauled their engineering operations to do this, but they have the battle scars to show for it. This is part of why we built our Engineering Management Platform.

Many potential customers assume Jellyfish insights (specifically Allocation) come from aggregating story points. While we can and do show insights around story points for teams who use them, we don’t need to do this to inform some of the more insightful metrics for strategic decision making. And when it comes to measuring engineering time allocation, we don’t. We’re able to measure our customers’ engineering effectiveness in time, specifically the efforts of full-time engineers (FTEs), without disrupting your current engineering workflows.

We use what we call “engineering signals.” Commits and pull requests in Git and assigned/resolved tasks in Jira are examples of what we call signals. These are specific actions taken within the tools and platforms developers already use that give us information about what teams are working on. We take these signals, combine them with contextual business data, and visualize them in a comprehensive way to show what your teams are working on. We not only use these engineering signals to provide work Allocation insights, but we also use this methodology to provide productivity and efficiency insights too.

In short, story points have a purpose, but leaders should not use them in all instances just because that’s what they can measure today. We built our Engineering Management Platform to elevate the practice of engineering management, and that requires looking to the future of what should be measured by engineering leaders. This is why we have invested so heavily in our data science, our engineering signal processing, and our work allocation model: The future of engineering management requires it.