In this article

Platform engineering went from niche practice to mainstream strategy in just a few years. According to Gartner, 80% of large software organizations will have platform teams in place by 2026.

But you can’t just hire a few engineers and hope for the best. You need a clear structure and the right roles. Many organizations still struggle with the basics, like this engineering leader on Reddit:

And no, you can’t just rebrand your DevOps team and expect different results.

Platform engineering teams aren’t traditional ops teams. They’re product teams building tools for internal customers (your developers). They need different roles, a different structure, and a different mindset.

This guide covers the key roles you need, how to structure the team, and how to approach platform engineering as a product discipline.

Whether you’re hiring your first platform engineer or restructuring an existing team, here’s what you need to know.

What Does a Platform Team Actually Do?

What Does a Platform Team Actually Do?

Before you build a platform team, you need to understand what it does. The work breaks down into a few core areas that directly impact how fast your developers can ship.

Infrastructure as Code (IaC)

Why this matters for developers: Developers need databases, queues, and cloud resources to build features. Without a standardized infrastructure code, they either write Terraform from scratch or wait days for ops tickets.

How the platform team handles it: The team builds reusable, scalable IaC modules for common infrastructure patterns. Developers select pre-built templates through a portal and deploy vetted, production-ready infrastructure.

Example: A developer needs a PostgreSQL database for a new microservice. They open the internal developer platform, select “Managed PostgreSQL,” choose their environment and specs, and click deploy. Five minutes later, they have a fully configured database with backups, monitoring, and security policies already set up.

Container Orchestration

Why this matters for developers: Developers write code that needs to run reliably across different environments. Managing Kubernetes clusters, writing deployment configs, and troubleshooting pod failures distract them from building features.

How the platform team handles it: The team sets up and maintains the Kubernetes infrastructure with sane defaults. They provide deployment templates and abstractions so developers can ship containers without learning every single Kubernetes concept. An engineer on Reddit described how their team handles this exact problem:

Example: A developer finishes a new service and wants to deploy it. They define basic requirements in a simple config file (memory, CPU, replicas) and push their code. The platform handles the rest – creates the pods, sets up health checks, configures autoscaling, and exposes the service. The developer never touches a Kubernetes YAML directly.

Continuous Integration and Delivery (CI/CD)

Why this matters for developers: Every code push should trigger automated builds, tests, and deployments. When developers have to manually configure pipelines or wait hours for builds, they ship more slowly and constantly context-switch. One developer on Reddit summed up the pain perfectly:

How the platform team handles it: The team builds standardized CI/CD pipelines that work out of the box for most services. They maintain the tooling, optimize build times, and create deployment workflows that balance speed with safety.

Example: A developer pushes code to their feature branch. The pipeline runs tests, builds a container, and deploys to a preview environment, all within a few minutes. When they merge to main, the same pipeline deploys to staging, runs integration tests, and promotes to production with a single approval. No pipeline configuration needed.

Monitoring and Observability

Why this matters for developers: Developers need to know when their services break and why. Without proper monitoring, they find out about issues from angry users or spend hours digging through logs to debug problems.

How the platform team handles it: The team provides pre-configured monitoring that captures logs, metrics, and traces automatically. Every service gets baseline dashboards and alerts without extra setup work.

Example: A service starts throwing errors at 2 AM. The on-call developer gets an alert with the error rate, affected endpoints, and a link to relevant logs. They open the tracing tool, see exactly which database query is timing out, and spot the issue in minutes instead of hours.

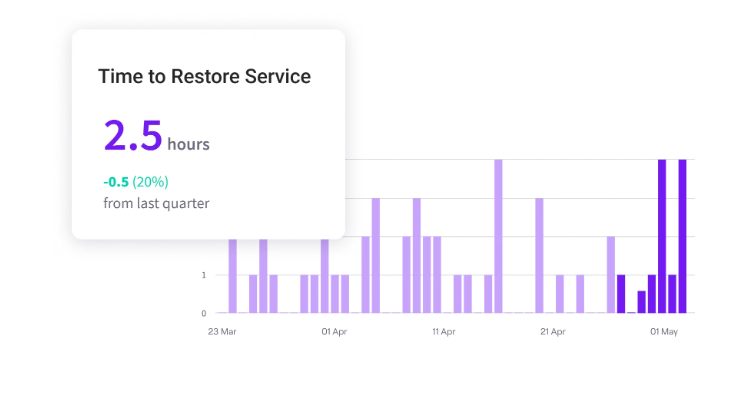

PRO TIP 💡: You can use Jellyfish to measure how fast teams recover from incidents before and after you deploy better monitoring tools. Jellyfish automatically tracks MTTR by pulling data from your incident management systems.

Security and Compliance

Why this matters for developers: Every service needs proper authentication, encryption, and access controls. Developers shouldn’t have to research security best practices or remember compliance rules for every single deployment.

One developer on Reddit described how most teams simply aren’t set up to teach or enforce secure coding practices, which is why platform-level guardrails matter so much:

How the platform team handles it: The team provides secure defaults and automated checks that catch issues before production. Developers work within guardrails that enforce security and compliance without slowing them down.

Example: A developer needs to store API keys for a third-party integration. The platform provides a secrets management service with encryption and access controls built in. They store the secret through a simple CLI command, and the platform handles rotation policies, audit trails, and access restrictions. An automated scan also flags an outdated library version with security issues before the code ships.

Core Roles and Skills of a Platform Team

Core Roles and Skills of a Platform Team

You can’t build a platform team by hiring only DevOps engineers or SREs. These teams need a mix of both technical skills and product mindsets.

Here are the core roles you should consider:

The Platform Product Manager (PPM)

The platform product manager (PPM) might be the most important hire you make for your platform team. They own the platform roadmap and treat your internal developers as customers.

As one engineer on Reddit pointed out, platform work only succeeds when the organization recognizes it as a long-term investment:

Platforms are LONG-TERM bets. If your leadership isn’t “platform-minded”, getting buy-in for continued platform investment is a long, frustrating, and unrewarding journey.

This role bridges the gap between what engineers want to build and what developers need to ship faster. Core responsibilities include:

- Maintain the platform roadmap: The PPM owns the platform’s direction and prioritizes functions based on developer impact. They decide what gets built, when, and why.

- Collect developer feedback: They run regular check-ins with engineering teams to understand what’s broken or slow. This direct line to users keeps the roadmap honest and prevents the team from building in a vacuum.

- Define and track success metrics: The PPM tracks how many developers use the platform, how happy they are, and whether they ship faster. These numbers justify the platform’s existence and guide what to build next.

- Bridge platform and product teams: They translate what developers need into specs that the platform team can build. They also explain what the platform offers back to product teams so everyone knows what’s possible.

- Make build vs. buy decisions: The PPM evaluates whether to invest months building something custom or adopt an off-the-shelf tool. They consider engineering bandwidth, timeline pressure, and whether the team wants to maintain this forever.

Strong PPMs typically come from software engineering roles where they shipped code and dealt with infrastructure pain themselves. This history matters because many platform engineers won’t respect someone who doesn’t understand the technical work.

But they also learned product management – how to research user needs, build roadmaps, and communicate value to non-technical stakeholders. They speak both languages fluently.

Infrastructure Platform Engineers

Infrastructure platform engineers build and maintain the core infrastructure that powers the platform. They handle the heavy technical work – Kubernetes clusters, IaC modules, CI/CD pipelines, and the background systems that developers interact with.

Their main responsibilities are usually to:

- Build reusable infrastructure modules: They create IaC templates and modules that abstract away complexity for developers. These components get reused across teams, so one engineer’s work benefits dozens of developers.

- Maintain platform infrastructure: They keep the underlying infrastructure healthy – Kubernetes clusters, cloud resources, and networking. When something breaks at 3 AM, these engineers diagnose and fix it.

- Design self-service capabilities and interfaces: They build the APIs, CLIs, and web interfaces that let developers provision infrastructure on their own. The aim is to remove ticket queues and waiting periods entirely.

- Optimize costs and performance: They analyze spending patterns, kill zombie resources, and tune systems for efficiency. They balance cost reduction against performance needs so neither suffers.

- Implement security and compliance controls: They embed security best practices into infrastructure code and enforce policies through automation. Developers get secure infrastructure by default.

Infrastructure platform engineers typically have strong backgrounds in DevOps, SRE, or systems engineering. They have expertise in orchestration platforms and infrastructure automation.

DevEx Platform Engineers

DevEx Platform Engineers focus on the developer-facing side of the platform. They build the tools and workflows that developers interact with directly (e.g., internal developer portals, CLI tools, documentation, and integrations).

Some of their main responsibilities are:

- Build internal developer portals: They design and build the web interfaces developers use to interact with the platform. The goal is to make capabilities obvious and resources easy to provision without scrolling through wikis.

- Develop CLI tools and SDKs: They create command-line tools that match developer workflows. Developers should be able to deploy, configure, and debug from their terminal without opening a browser.

- Create documentation and onboarding materials: They write guides, tutorials, and references that explain how everything works. Clear documentation reduces the “how do I…” questions that flood team Slack channels.

- Integrate with developer tools: They connect the platform to GitHub, Slack, and other tools developers use daily. A successful platform should meet developers where they work, not force them to learn new workflows.

Many DevEx platform engineers tend to come from frontend or full-stack backgrounds, where they have already built user-facing products. They understand both the technical platform pieces and how developers think and work.

The best ones obsess over small details (such as keyboard shortcuts or loading states) because they know that even those tiny details can determine whether developers love or avoid the platform.

PRO TIP 💡: You can rely on Jellyfish DevEx to measure how developers experience your platform through research-backed surveys. Teams can track satisfaction scores for specific platform features, like your internal developer platform or CLI tools, and connect survey responses to developer productivity metrics.

Finding the Right People (The Hiring Challenge)

Finding the Right People (The Hiring Challenge)

Platform engineering is still a young discipline without a clear talent pipeline. Post a “platform engineer” job, and you’ll get applications from DevOps engineers, SREs, and full-stack developers, all with different interpretations of what the role means.

This isn’t surprising when you look at community discussions. In one Reddit post, a DevOps engineer said they keep seeing the term everywhere but still don’t know what it really refers to:

Most qualified candidates don’t search for “platform engineering” jobs because they identify with other titles. This makes hiring harder than filling traditional engineering roles, where everyone understands the job description.

Here are some places where you can look for talent:

- Internal transfers from DevOps or SRE teams, especially engineers who’d rather build tools than respond to tickets

- Senior engineers who’ve been pushing for better developer tooling and self-service infrastructure

- Engineers from companies with mature platform teams like Netflix, Spotify, or Google (expect competition and higher compensation)

- Backend engineers with deep cloud infrastructure knowledge who understand both software development and operations

- People who contribute to platform-related open source initiatives like Backstage, Crossplane, or Kratix

Infrastructure knowledge gets people in the door, but it’s not enough. The best platform engineers combine infrastructure expertise with product sensibility and user empathy.

They need to explain complex technical tradeoffs to non-technical leaders and collect feedback from skeptical developers. Strong candidates also know when “good enough now” beats “perfect eventually.”

Watch out for these warning signs during interviews:

- Pure ops backgrounds with no development experience (they struggle to think like product builders)

- Engineers who only chase new projects and show no interest in maintaining or improving existing tools

- Candidates who speak only in technical terms and can’t explain why something matters to the business

- Anyone who complains about developers “not understanding how things work” instead of seeing that as a design problem

- Engineers who measure success by technical metrics (uptime, performance) but never mention user satisfaction

Hiring for platform roles takes longer than traditional engineering positions, but it’s worth the wait. One engineer with the right mindset can have more impact than three who only care about infrastructure.

Structuring Your Platform Team for Success

Structuring Your Platform Team for Success

Team structure and reporting lines determine whether your platform team can maintain a product roadmap or get consumed by ad-hoc requests and operational work.

Team Topology: Building Around Capabilities, Not Technologies

You can hire brilliant engineers and still build an ineffective platform team if the structure is wrong. Platform team members need to operate like product teams, which means structuring around what developers need, not what technologies you run.

Team Topologies offers the clearest framework for this. Product teams are “stream-aligned teams” that ship features to customers, while platform teams support them by taking infrastructure headaches off their plate. They create golden paths – curated tools, APIs, and templates that make common tasks simple and self-service.

The typical mistake is organizing by technology stack:

- Individual application development teams own Kubernetes, Terraform, monitoring, and networking separately

- Developers file multiple tickets and wait on multiple teams for simple tasks

- Structure built around your technology preferences instead of user needs

- Your technical boundaries become friction points for everyone else

The better approach is to build cross-functional teams that own complete developer experiences. Take “New Service Creation” as an example. A single team with a platform product manager, infrastructure engineers, and DevEx engineers runs that entire workflow from end to end.

This structure puts developers first. They don’t care that Kubernetes and Terraform are different technologies, but about shipping a new service fast.

Where Platform Teams Should Report

Where platform teams report determines how much autonomy they have and whether they can execute on a real roadmap. Without the right reporting structure, they become glorified ticket handlers who respond to whoever complains loudest.

Here are the three most common reporting models:

- Under the CTO or VP of Engineering: Platform reports at the same level as other engineering teams. They get executive visibility and organizational weight, but leadership must actively protect them from becoming the catch-all team for every infrastructure request.

- As a separate product organization: Platform gets its own dedicated leader (VP or director) who reports to the CTO. This structure reinforces the platform as a product philosophy, complete with its own roadmap, though it risks creating silos between the platform and the teams they support.

- Embedded within Infrastructure or DevOps: Platform rolls up through ops management. This structure usually struggles because operations teams optimize for stability and incident response, leaving platform development lifecycle work sidelined.

The best structure depends on your company’s size and engineering culture. Smaller companies (under 50 engineers) often start with platform reporting through engineering leadership.

Larger companies (100+ engineers) usually see better results when the platform has its own leader who shields the team from competing priorities and secures the resources they need.

What matters most: Regardless of structure, platform teams need a leader who thinks like a product manager, pushes back on bad requests, and has organizational weight to get resources. Stay away from matrix reporting models. When platform engineers have dotted-line relationships to multiple teams, there’s no accountability.

PRO TIP 💡: Jellyfish resource allocation metrics show where platform team time goes in detail. Track how much effort your platform team spends on roadmap work versus unplanned tasks or support tickets.

External Interaction Model: Managing Stakeholders

Set up clear communication channels from day one. Schedule office hours, set up dedicated Slack channels, and hold quarterly roadmap sessions where developers can provide input. Without these channels, you’ll get drive-by asks in the hallway and urgent emails from VPs.

One engineer on Reddit described how simply formalizing Slack communication helped them understand what developers actually needed:

One thing I found really useful in this transition was setting up feedback loops to get a sense of what work would be most beneficial. We created a #help-* channel in our Slack workspace to handle support requests, which were super revealing about what was needed.

You need to handle inbound requests with a structured process:

- Create an intake form or ticketing system so requests don’t get lost in Slack threads

- Prioritizing requests through regular review sessions with your PPM making the final calls

- Communicate decisions transparently, especially when you say “no”

- Share your roadmap publicly, so teams understand what you’re building and when

Saying no is part of the job. Teams sometimes want specific solutions that work for them but create long-term maintenance problems for everyone else.

Your PPM should evaluate requests based on the general platform strategy, not which VP sent the email. And when you reject something, share your reasoning and point toward alternatives.

The Cultural Foundation for Success

The Cultural Foundation for Success

The platform team needs a product mindset, not an ops mindset. Research what developers need, build features that tackle those inefficiencies, iterate based on usage data, and track whether people use what you create. The goal is to build tools that developers reach for voluntarily because those tools make their work faster and simpler.

This means there will have to be some specific mindset changes across the team:

- From gatekeeping infrastructure to enabling developers

- From “keeping things running” to “making developers productive”

- From default no to “yes, here’s how”

- From firefighting hero culture to shipping features that prevent fires

- From technical perfection to more practical solutions

Leaders set the tone by choosing what to recognize. Firefighting has its place, but building systems that prevent fires deserve more attention.

The same logic applies to building your team. Hire for technical ability, sure, but pair it with people who care about developer experience and listen to feedback.

Promote engineers who make everyone else better, not just the ones who solve impressive technical problems alone.

How Jellyfish Can Help

How Jellyfish Can Help

Your platform team ships tools that make other engineers faster. Great. But how much faster? Are teams using what you built, or are they finding workarounds?

These questions matter when you’re asking for more budget or defending why platform engineering deserves dedicated headcount.

And this is exactly where tools like Jellyfish help.

Jellyfish is an engineering management platform that analyzes signals from your development tools to show how fast teams ship, where engineering time goes, and which bottlenecks slow down software delivery.

- Understand platform adoption across the org: See which teams use your platform capabilities, which features they adopt, and where engagement drops to guide your roadmap

- Demonstrate faster delivery with DORA metrics: Measure deployment frequency, lead time for changes, and change failure rate to show concrete improvements after teams adopt platform toolchains.

- Evaluate AI assistant impact on workflows: Measure how AI coding tools affect developer performance within your platform and compare different tools to make informed purchasing decisions.

- Connect developer feedback to performance data: Link survey responses about platform experience directly to productivity metrics so you can prioritize fixes for complaints that correlate with actual slowdowns.

- Generate capitalization reports automatically: Create accurate, auditable software capitalization reports from engineering activity without timesheets or manual hour tracking.

- Compare performance against industry peers: Benchmark your platform metrics against other engineering organizations to show leadership whether your improvements match top-performing teams.

When you can show leadership that deployment frequency doubled or developer satisfaction jumped 40%, budget conversations get a lot easier.

Schedule a demo to see how Jellyfish tracks the metrics that prove your platform works.

FAQs

FAQs

What is the most important first hire for a new platform team?

Your first hire depends on your company’s maturity and what vulnerabilities you’re solving. If you already have some platform infrastructure but no strategy or product thinking, start with a platform product manager who can define what to build and why.

If you’re building from scratch and need someone to set technical foundations, hire a strong infrastructure platform engineer who understands both systems and developer needs.

The PPM route often works better because they can shape the vision and help you hire the right engineers afterward, but smaller companies sometimes need to prove technical value first before they invest in product management.

How is a platform team different from a traditional operations team?

The key difference is product thinking. Platform teams treat developers as customers and build tools to make them more productive (proactive approach), while operations teams maintain systems and respond to incidents (reactive approach).

Should our platform be mandatory to drive standardization?

No. Mandating platform adoption usually backfires. Developers find workarounds when forced to use tools they don’t like, and you lose the feedback that tells you what’s broken.

Build a platform good enough that teams choose it voluntarily because it makes their lives easier. The best standardization happens when your golden paths are so much better than alternatives that developers adopt them naturally.

What’s a good “first product” for a new platform team to build?

Pick a frequent, painful problem that affects multiple teams. New service creation works well – automate the repo setup, infrastructure provisioning, and CI/CD in one flow instead of making developers do it manually.

Standardized deployment pipelines are another strong choice if teams waste time managing inconsistent CI/CD. The point is to choose something where the improvement is obvious and easy to measure.

Learn More About Platform Engineering

Learn More About Platform Engineering

- The Complete Guide to Platform Engineering

- Platform as a Product: The Foundation for Successful Platform Engineering

- When to Adopt Platform Engineering: 8 Signs Your Team is Ready

- Platform Engineering vs. DevOps: What’s the Difference?

- Understanding The Platform Engineering Maturity Model

- How to Build Golden Paths Your Developers Will Actually Use

- Best 14 Platform Engineering Tools Heading Into 2026

- 8 Benefits of Platform Engineering for Software Development Teams

- 17 Platform Engineering Metrics to Measure Success and ROI

- 9 Platform Engineering Anti-Patterns That Kill Adoption

- The Top Platform Engineering Skills Every Engineering Leader Must Master

- 11 Platform Engineering Best Practices for Building a Scalable IDP

- What is an Internal Developer Platform (IDP)?

About the author

Lauren is Senior Product Marketing Director at Jellyfish where she works closely with the product team to bring software engineering intelligence solutions to market. Prior to Jellyfish, Lauren served as Director of Product Marketing at Pluralsight.